- Home

- Jonathan Reggio

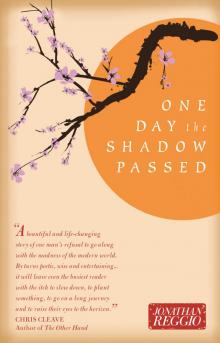

One Day the Shadow Passed Page 9

One Day the Shadow Passed Read online

Page 9

I could see the farmer and Mitsuo wending their quiet way through the misty orchard, two shepherds amongst their ever-trusting flock. As they walked they stopped and touched the trunks of the trees as if they were patting the flanks of their favourite horses. They reached up and pulled upon the outstretched boughs, as if they were shaking hands with old friends. I watched the farmer bend down and forage amongst the ground cover, inspecting leaves and searching for the friendly pests that he prized so highly and holding them up to show Mitsuo before replacing them on the same leaves from which he had just taken them.

The two men didn’t seem to be in a hurry. They looked like connoisseurs of some sort, as indeed they were, taking a leisurely stroll through a living art gallery.

Would the seed of a new kind of life, scattered here by the wind, take hold? If it were a question of purity of heart and purpose then I did not doubt it. The farmer was relying on his belief that the modern world was quite wrong and that mankind knew little about the true workings of nature. Only time would reveal if this conviction was enough.

All I could do was offer my friends one last silent prayer as the horse carried me through the low-hanging branches and slipped into the shadows of the wood. Was he a genius or was he a madman? And would I ever see him again? A verse of Basho floated into my mind and I bowed my head to its mournful power:

Separated we shall be

Forever, my friend,

Like the wild geese

Lost in the clouds.

I dearly hoped it would not be so but even if it were I was not leaving empty-handed, for although at the time I only partially realized it, I was carrying away with me back to Europe something almost as precious as friendship itself: the seeds of a new life.

As I finally lost sight of the farm and settled back into the rocking motion of the horse’s gait, I realized that I no longer needed to continue my pilgrimage and that it was time now to head for home.

Days and months are milestones of eternity, so are the years that pass us by.

It is hard to explain the transformation that had been wrought within me by going to Japan but on my return home I found that above all else I now wanted to work with people. A new sense of optimism had taken hold of me, a sense of optimism that I was desperate to communicate to others. I had rediscovered hope and I now knew that the world was not always as gloomy as it sometimes seemed.

I got a job as a teacher in a school, a job that I did for seven years. A schoolteacher’s life is busy and I had very little time to think about farming. To tell the truth, I was young and I was experiencing so many new things all the time and I was so full of the impatience and forgetfulness of youth that I didn’t realize the extent to which this change in my outlook on life was the natural flowering of a seed that had been planted during those twenty-four hours spent on a hillside in Japan.

Instead, I set my experiences with the farmer aside and got on with my life. All I knew was that the darkest days had finally passed and that my mood had changed for the better, but in my ignorance I put this down to fresh air and foreign travel in general and not specifically to my experiences at the farm.

As soon as I set foot on English soil again I instantly became caught up in all the normal complications of life that I had been unable to engage in for the past few years. Where was I going to live? What was I going to do with my life? How was I going to earn a living? Some of my friends had already established themselves in their careers and I needed to get going with mine. It was time to start afresh on the road of life.

During that first year after my return from Japan, if I did ever think of the farmer I thought of him as a dreamer, engaged in a brave but probably hopeless struggle against the problems of the world. But mostly, I didn’t think about him at all. I was simply far too busy.

It turned out that teaching was a good choice of career. I felt that I could contribute to the world by having a positive influence on my young students. I taught history and occasionally, when the syllabus permitted, I taught lessons on Japanese poetry.

Life was good but although I was more optimistic than I had been prior to my departure for Japan, deep down I could still never entirely throw off the same old feeling of unease, the feeling of unease that had prompted my original journey.

For what kind of world would the children I taught actually inherit? And what about their peers all around the world? What about the less fortunate children who woke every day into the grim realities of supposedly positive words like “globalization” and “growth”?

And as the years went by I found myself wondering more and more about what might have happened to my friend.

It was in the classroom that memories of the farmer returned most often. Children have a special facility for asking awkward questions and it is the teacher’s lot that he or she has to learn how to answer them. Every teacher finds their own way to respond to such questions as: “If humanity is meant to be progressing then why are we destroying the world around us?” or: “Why are some people starving to death when we have so much food?” or: “If science and technology are meant to improve the world, why is it more dangerous than ever?”

It was at times like this that I sometimes found myself thinking of the farmer and his life, and slowly but surely questions of my own began to work away at the back of my mind. Could he have actually done it? Could he have succeeded or was the farm now nothing more than a stretch of overgrown, weed-covered fields? And was he now a married man, or had the barley harvest failed the following spring?

I wanted to tell the children about the farmer and to urge them not to lose faith in the world. I wanted to explain that there were other ways of living; that the farmer had chosen to walk one of these paths and it had brought him harmony and happiness.

But, as I didn’t know if he had succeeded or not, I couldn’t in good conscience hold him up as an example of a new life. As it was, his existence would have sounded like something out of a fairy tale to them and, until I knew one way or another if he had succeeded, I would have to regard his struggle as nothing more than a dream.

But as time went by I knew that it was becoming increasingly important for me to learn what had become of him. I contemplated going back there, to find out what had happened. But then I always stopped myself – it would simply be too much for me to bear to find out that this brave man’s efforts had been in vain and that the place where I had spent that magical period of time no longer existed at all. I grew to dread the possibility that a commercial farm now stood in its place with its monotonous acres of machine-harvested rice and parade-ground ranks of doctored trees; and that the farmer too had long departed, forced to work with machines on another farm, or worse still to find work in the city itself.

In any case, I was at the beginning of my career and I was far too busy to go and find out what had happened over the ensuing years. Besides, as long as I didn’t know the truth, I could at least still hope.

As is the way with life I found myself slowly climbing the ladder of my chosen career and as every year passed I took on more responsibility and began to grow into a middle-aged man. Life continued in this fashion until at the end of my seventh year at the school I was offered a sabbatical, which I duly accepted. I had some savings and I hadn’t been abroad for many years so I had a great desire to breathe a little pure air. I decided that it would be a good time to return to Japan. Without any preconceived notion beyond that, I struck out again for the ancient Buddhist pilgrimage trail around the Island of Shikoku where I had had the extraordinary experience all those years before.

The country had changed. As soon as I set foot in Tokyo I could see and hear and feel the stirrings of progress all around.

There were many more cars on the streets of the capital and many more people were wearing Western clothes. There were advertising billboards tempting people to buy white goods and new household products, and everywhere I turned traditional buildings were being pulled down and replaced by new structures made fro

m concrete and steel.

In the shops, people could buy things that they would never have thought of owning before: gramophones, vacuum cleaners and even leather armchairs, which was especially strange as Japanese people still, almost without exception, sat on the floor on Tatami mats.

I recognized too that a new Western scale of values was being used by the average Japanese man or woman. People wanted to buy things because they were new and not because they needed them.

Outwardly at least, Japan appeared to be striding happily into a future of Western-style industrialization. The government, which had always in the past been so scornful of the materialism of Western culture, now seemed to have decided actually to hold it up for admiration.

I knew that things weren’t that simple of course. The catastrophic shock that had been dealt to the foundations of the old order by the dropping of the atom bombs, combined with the presence of the victors, living as an occupying force, making laws and refashioning society, had destroyed a lot of the Japanese people’s ancient self-confidence.

The whole place left me feeling bewildered. So many good things were being jettisoned as part of the general clearing out of the old samurai culture and so much bad seemed to be coming into Japan. And of all the things that I held dear about Western society and that I thought would be most worthy of export, none of them seemed to have made their presence felt at all.

When I finally reached Shikoku on my third day in the country I was dizzy with all the changes and all the more eager to get out into the tranquillity of the remote countryside.

My plan was somehow to make my way to the little village of Fumimoto and from there ask directions to the farm. After that, whether the farm existed or not and whether or not I was reunited with my old friend, I would return to the pilgrims’ trail and finish the walk that I had begun all those years ago.

I had assumed that I would have to catch a train to the southern end of the island and then make my way from there, but I found instead that there was now a sophisticated bus network connecting all the outlying regions of the island and that I could catch a bus the following morning and be at my destination by late afternoon. How times had changed: ten years ago, this journey alone would have taken at least three days.

Throughout the night in Matsuyama I was filled with a growing sense of foreboding. What if the farm was no longer there? Whilst this possibility had remained in the abstract I had been able to keep the potential consequences of this eventuality from my thoughts, but now that I was actually going to discover the truth the following day, I became agitated beyond belief and was unable to sleep the whole night long.

Without my realizing it, over the years the farmer’s struggle had somehow gained a great personal significance for me. As long as I knew that there might be one person left in the world who had successfully demonstrated that there was another, better way of living then I could still have hope. But if it now transpired that the farmer and his farm had vanished like a snatch of summer dreams and that there was finally nothing left for me in this world other than the bleak mantras of science and progress, my spirit would be shattered into a thousand pieces.

I seriously contemplated turning back and returning to Europe on the next flight just so that I could maintain my state of ignorance, but when the first slivers of grey light appeared at the edges of the curtains in my little hotel bedroom I realized that I had no choice but to go on. I went to the bus station and got on the bus and found myself a seat at the back by the window where I dozed my way through the first hours of the new day.

By late afternoon we were driving through scenery that I should have recognized from before for we were now approaching Fumimoto and this was the land that I had patiently trodden on foot. But the small farms had almost all disappeared – replaced instead by gigantic acres of machine-farmed land. The hamlets were quieter and some of them even had a noticeably sad air about them. There were fewer children running in the meadows, fewer dogs and horses in the streets everywhere I looked, and there were machines doing the work of men. The workforce itself had been decimated.

I got off the bus at Fumimoto and was struck by the calm of the place. When I had first entered the village on horseback, fresh from the farm all those years ago, it had been buzzing with life, but now it appeared empty and desolate. There were one or two people in the little main street, but none of them seemed to want to meet my gaze.

I took this all to be a very bad omen and as I started to get my bearings a feeling of queasiness began to overtake me. I had come so far and waited so many years and yet now it seemed once more as if all my hopes had been misplaced. I gritted my teeth and made a private vow: this truly would be the last time I would ever allow myself to believe that there could be alternatives to the ever-turning cogs of the modern world. From this day forth I would put my head down and toe the line. If I didn’t like the way the world was going that was my fault and no one else’s: there could be no other way.

Half-way up the street I recognized the track by which I had entered the village all those years ago. I peered into the cool shade of the wood: the track was still in use. That much was for sure. There were fresh hoof marks and cart rucks. But then nothing could be read into that. The track led to other places too, not just the farm.

I adjusted my backpack and looked around. Down the street, past the side of one of the houses, I could see an old villager fitting a bridle to a horse. I took a deep breath and made my way over to him. The villager stopped what he was doing and looked at me whilst with one hand he calmed the horse by stroking its mane.

I greeted him in Japanese. His response seemed friendly enough, though I couldn’t understand his rural dialect. My Japanese was very rusty and I tried in several different ways to ask him about the farmer but he simply grinned back at me and shook his head in incomprehension.

Finally, I delved into my bag and found a pen and a piece of paper and, working as carefully as I could, I wrote out the Japanese characters that spelt the farmer’s name: Takeshi Fumimoto. A look of instant recognition lit up the old man’s face and he immediately pointed back towards the track through the wood and muttered something that I couldn’t understand and then slapped his hand on his horse’s flank and made a gesture that seemed to suggest that he would take me there. He continued to chatter in dialect whilst he finished the job of readying his horse, and then when everything was prepared he motioned for me to climb up onto the cart. I hauled myself onto the single wooden plank that was the seat and slung my backpack into the empty cart. The old villager climbed aboard and with a twitch of the reins we were underway.

What this all meant I did not know. I had already spent so much time speculating about the fate of the farm that I was not going to spend another second trying to read anything into the gestures and actions of the old villager. He had recognized the name of the farmer and that was all. It didn’t mean that the farm was still there, it didn’t mean that the old stone farmhouse was anything other than a derelict ruin, and it certainly didn’t mean that the farmer was living a happy life married to his true love.

Perched on the hard wooden seat, bouncing along the uneven track through the cool wood, with the old villager occasionally muttering something to himself, I tried to relax and put myself into a state of mind where I would be indifferent, no matter what I was about to discover.

But as the cart made its final turn over the brow of the wooded hill I was left speechless with amazement.

Before us on the road, two children were playing, skipping like lambs, back and forth through the farmyard gate. I was so astonished by this unexpected sight that all I could do was stare at them as if they were unicorns.

But when I noticed in the distance that there were three young men walking back from the fields below the house and two further people in the orchard to our right, my astonishment turned to wonder. I spun my head this way and that and saw other figures hard at work on the slopes of the orchard. Five, ten, fifteen people, men and women,

young and old, more than I could count. I scanned the far slopes of the hillside, searching for the barren land where all those years ago I had passed the morning, scythe in hand, but all I could see were luscious orchards. I hunted in the fields to the north, expecting to see the black lands where the harvest had failed, but all I saw were swathes of golden rice plants rocking gently in the summer sun.

The farm had been reborn and everywhere I looked nature was in full bloom, everywhere there were people working in the fields and from the chimney of the farmhouse a column of smoke rose into the still morning air. More than any flag could be, it was a declaration of habitation and life.

The villager touched the reins and the cart drew to a halt just up the track from the farmyard gate. The old man pointed ahead with outstretched arm and nodded.

“Fumimoto-san.”

I transferred my gaze from the riot of nature all around me to the farmyard. There I saw for the first time in seven long years my friend the farmer. He was as busy as ever, stooped over a box of freshly picked fruit, sorting it into different sizes. My heart filled with joy and I leapt from the cart, forgetting even to grab my backpack, and bounded down the track.

As I entered the farmyard, the two children began to chatter and laugh. They scampered over to the farmer’s side and tugged his clothes. He looked up from his work to see what all the fuss was about. He had not changed at all. He looked just as youthful and vigorous as when I had first set eyes on him all those years ago.

When he saw me his face lit up in an enormous smile. He wiped his hands on his shirt and without hesitating for even a second he walked straight over. We met in the middle of the farmyard and embraced.

“James! I have been expecting you. I knew you would come …”

One Day the Shadow Passed

One Day the Shadow Passed