- Home

- Jonathan Reggio

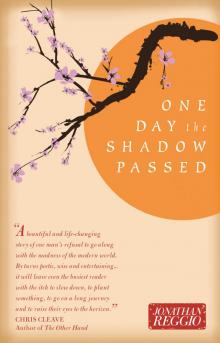

One Day the Shadow Passed Page 2

One Day the Shadow Passed Read online

Page 2

Some people say that when you lose your way you do so for a reason. Your deeper mind, which is better attuned to the truth of the world than your conscious mind, has decided that your life is heading in the wrong direction and that something must finally be done.

Unconstrained by time and space your deeper mind works out a new plan that will take you back to the source of all truth, for it views your conscious mind as a wayward younger sibling who sometimes needs to be guided back on track. More often than not it neglects to explain its plan, knowing from bitter experience that the conscious mind will ignore and overrule its seemingly irrelevant advice.

But if I had not strayed from the path to the temple I would never have wandered into the wood; I would never have known the tastes of its exquisite wild fruits; I would never have stumbled upon the magical orchard; and my life would have continued on down its well-trodden path. But instead I had let myself stray from that path and now I found myself wandering alone through a wild orchard.

About twenty yards away, crouching amongst the undergrowth at the base of a citrus tree, was a man. He could not have been more than thirty years old, probably younger, but because of my relative youth he seemed old to me. I was very relieved to see another human being. As I approached him, I hailed him in my rudimentary Japanese. Alert as a rabbit, his head shot up and turned to find the source of the voice. He must have been very surprised to see a stranger appear from the bushes, doubly so as I was a foreigner. Much to my amazement he answered me in accented, but otherwise perfect English.

“Hello. Are you lost?”

He was short and wiry but he moved with enormous vitality. In a second he had slipped through the trees and come closer to inspect me better. He was wearing traditional clothes: cotton shirt and trousers, and sandals made of plant fibre; he looked as if he had stepped out of a painting from the Tokugawa period. His bright eyes regarded me with curiosity. Much relieved that we could speak in English, I tried to explain my predicament.

“Yes. I’m lost. I have no idea where I am.”

The sound of my own voice surprised me. I suddenly realized that not a word had passed my lips for several days.

“I am walking the pilgrims’ route. I ran out of water and I think I might have strayed from the path. The next stop was supposed to be Kashinoki. I’m sorry to walk into your farm like this.”

The farmer was clearly a shy man, for now that he was standing close to me he didn’t look me in the eye at all but tilted his head down and seemed to look past me. Despite this, he spoke to me with a smile on his face.

“Kashinoki is not so far from here. But it’s too far to walk now.”

I had grown up in Oxford, but had spent many of my childhood holidays in my uncle’s cottage in rural Scotland and so was used to the ways of those who lived their lives in the outdoors. The farmer’s combination of an awkward manner and decisive speech reminded me of so many of the country folk that I had met whilst roaming the Highlands.

“It will be dark in twenty minutes. Come – you can stay on my farm.”

With an enormous sense of relief I accepted the farmer’s generous offer and followed him down the path that wove its way through the orchard. It was good to be out of the wood and a farmhouse would make a welcome change from a temple floor.

The farmer spoke little as we walked. He looked this way and that, casting his eye over the orchard and occasionally pausing to inspect the leaves of the trees or examine the undergrowth at our feet. I walked several paces behind him, envious of his easy gait. My shoulders were sore from the rubbing of the straps of my backpack and my feet hurt. He seemed to glide through the orchard like a forest sprite.

When we arrived at the farm buildings, he explained that he slept in the mud-walled hut opposite the stone farmhouse, but that I could sleep in the main building next to the hearth. I can’t remember why now, although it was clear to me straight away that this was his family farm, he must have been born under the eaves of the farmhouse, and his family must have lived there for centuries.

The farmhouse itself was in impeccable order: the dishes were washed, the floor swept and there was not a speck of dust to be seen anywhere. The sight of a cooking pot and a neat pile of eggs and freshly picked vegetables cheered my spirits, and it was only then that I realized how hungry I was. Cooking utensils were neatly stacked next to the hearth.

I removed my boots. He placed a wooden water pitcher next to me and offered me peach tea from a pot that hung over the fireplace. I noticed then that his skin glowed with good health, his buttons were solidly sewn and his clothes were looked after with such care as to make them appear to be almost brand new.

He said that he had work to finish in the orchard before dinner and that I should make myself comfortable. I sat down, barefoot, nursing the delicious tea between my hands and enjoying the sense of peace provided by the stone walls, the small fire and the modest furniture.

It was a relief to be out of the woods and now that I had water in my belly and the prospect of dinner and even a bed for the night, my mind began to relax. Looking around me I started to wonder about the farmer and his life. Did he have a wife? It would be most unusual for someone of his age to live alone. Where were all the farm workers? And why was the orchard so wild and unkempt, so unlike all the other orchards that I’d seen on Shikoku? He clearly worked hard and was tidy, that much was certain. His home habits and self-discipline appeared to be as ascetic as those of the monks in their temples back on the path. And as for his perfect English, that was indeed a mystery.

“My name is Takeshi Fumimoto.”

The farmer was smiling at me, looking down at me from above. I had fallen asleep in front of the fire.

“This is my family farm. I am from the village of Fumimoto, which is two miles away, down the hill and along the valley. It is an honour to have a pilgrim in my house.”

I lifted myself hurriedly onto my elbow with an embarrassed smile and shook the sleep from my head. The farmer raised his right hand very gently as if to stop me and smiled. He had a kind, peaceful face.

“It is good to rest. Walking the pilgrims’ route is hard in September. Too much sun. I am preparing some dinner. You must be hungry.”

He deposited something at my feet.

“Here are some slippers. The biggest I could find.”

Outside I could see through the windows that the sun was now low in the sky. Despite my hunger I felt refreshed and so sat up and in a gulp finished the remains of my now cold peach tea. The farmer looked at me as a doctor looks at a patient.

“More?”

“No. Thanks. It was lovely. And thank you for the slippers.”

We sat in silence for some time whilst he prepared and chopped vegetables for the pot. The farmer, and indeed the entire farm, seemed to exist in a state of incredible peace.

I was very lucky, I reflected. Not many of the farmers round here would have taken me in and I was quite certain that there wouldn’t have been another farmer for miles around who spoke English. Farming anywhere in the world was a tough business and rural people by nature were cautious, suspicious folk. Furthermore, even in Tokyo, let alone in the wilds of the Japanese countryside, foreigners were regarded with ambivalence at best. They were strange beings, responsible for the humiliating defeat of the Emperor in the war, and they were also the bringers of a new and deeply unsettling way of life.

I could contain my curiosity no longer.

“Forgive me for asking, Fumimoto-san, but how is it that you speak such perfect English?”

For a second the farmer’s gentle gaze lifted from his work before returning quickly to focus on the pot. Without looking up again he spoke solemnly.

“Please, call me Takeshi. What is your name?”

I had disturbed the perfect calm of the peaceful stone room with a question. Now, clearly he felt justified in encroaching on my privacy by asking me my name. I felt ashamed of myself. I had been so wrapped up in my thoughts that I hadn’t introduced

myself before.

“I’m so sorry. My name is James.”

The farmer’s eyes flickered up again. He smiled at me briefly.

“Like the Saint James. The patron saint of pilgrims.”

I laughed with surprise.

“Yes. But how do you know that?”

The farmer paused in his work again and, with a knowing smile, for the first time his gaze stayed on me.

“Now I have two questions to answer. I will answer them both together: I was taught English by a priest, a missionary who lived in the village.”

He continued to stir the pot and added as an afterthought: “I was also trained as a scientist several years ago.”

We fell into silence once more.

“May I have some more tea?”

The farmer put down the knife he was using and began to move towards the hearth. Quickly, I jumped up and unhooked the kettle from its hanger above the fire.

“I can get it. Would you like some?”

He smiled at me warmly.

“No thank you. I have some here.”

I poured out the tea, replaced the kettle on its hanger and sat down again in silence. The company of this man brought me a feeling of immense peace.

Over dinner I volunteered a few observations on the countryside through which I had passed that day and I told him a little about my life. I was hoping that if I talked he might venture his own opinions, but for whatever reason he chose not to. He listened with interest and nodded politely but didn’t tell me anything more about himself.

After dinner he tidied up, refusing all offers of help. His only question was to ask, with a very grave expression on his face, if I had enjoyed the meal.

“It was delicious,” I said with genuine enthusiasm, picking the last grains of rice from the inside of my rice bowl. This answer pleased him greatly.

“It was all grown here: the rice from the fields below, the vegetables and the seven herbs of spring from the orchard above. The only things that were not grown here were the soya beans for the soy sauce. Right now it is not practical to make it on the farm. There are not enough people.”

For a second I thought that I caught a sad look on his face, but he turned back to his work, replacing the cleaned and wiped pans in their proper places by the hearth. Something about this curious man intrigued me and I wanted to learn more. He seemed to exude self-assurance; I can’t explain quite why I thought so but, in a way that is absent in most people, I felt that he seemed to know exactly why he was here on earth.

My enthusiasm for the food was real.

“The hard-boiled egg was exquisite. It reminded me of the eggs that I had in my childhood. For some reason they don’t taste like that any more. Neither here nor back home.”

He stopped what he was doing and graced me with his steady profound gaze.

“The eggs come from my hens. They are an old Japanese breed called Black Crow. I think I am the last person in Ehime Prefecture to keep them, maybe the last person on Shikoku. If that is the case then I am also the last person in Japan. They are small and skinny. They wander through the orchard and provide me with free manure … and they have a special trick. They peck the insects off the leaves without damaging the plants at all. They turn the pests into food for the vegetables.”

Suddenly he caught himself and fell silent, but there was something about his clear way of speaking that had given me a glimpse out over the landscape of his life. It was as if clouds had parted momentarily, uncovering a wonderful mountain-top view before closing again in darkness. I wanted him to speak. I was intrigued to hear his thoughts. I knew that if I stayed on the subject of farming he would talk.

“But why does no one else keep the Black Crow any more?”

He paused again as if he was choosing his words very carefully, suspecting correctly that I knew nothing of farming or nature.

“The new chickens lay many more eggs. But they get fed with feed pellets and are kept in coops day and night. It is not just the big farms that do that. Even on the family farms they would rather toss out a handful of pellets than risk them wandering around and getting eaten or lost.”

I felt, quite distinctly, that although this man was talking about hens, he was in fact telling me about something else, something of far greater significance, which had enormous implications for myself and indeed for the whole world.

“But after two summers they stop laying, whilst the Black Crow continue for years. When the time comes, the farmers cook the hens in a pot. Why do they stop laying? The farmers do not know or care. The hens are cut off from nature on all sides. Who can finally tell?”

He took my plate and cup.

“I’m glad you liked your dinner. I have a little work to do. Please have some more tea or sleep. I will try to be as quiet as possible.”

Leaving me by the hearth, he tidied up the last things and then sat down at a small wooden work table in the corner of the room.

The rest of the evening was spent in almost complete silence. At the table, the farmer took out a box that contained many small bags. Each bag held a different type of seed. One by one, he emptied each bag onto a different dish before carefully arranging the dishes in a row on the far side of the workbench. I poured myself some more tea and took out my diary, but I wasn’t really in the mood for writing.

With all the seed dishes arranged, he left the room through the door into the garden and came back a moment later carrying a large earthenware jar. Removing the lid from the jar, he fished his hand inside and took out a glistening lump of clay, which I suspected he had dug up from the hillside. He pinched off a piece of clay in his fingertips and then proceeded to take a seed from each dish and embed it within the moist clay before rolling the whole concoction very gently between the palms of his hands.

Tentatively, I asked him what he was doing and he muttered one word only: “Seedball”. He was deep in concentration. I wanted to offer my help, but I thought that if I asked he might feel bound to let me try and then I would slow down his whole operation whilst he tried to teach me what to do. He worked with speed and delicacy and I didn’t see him drop a single seed, even though many of them were extremely small, and he worked at his task for more than an hour.

Finally, having filled a large bamboo basket with seedballs, he returned the remaining seeds to their bags, put the bags back in the sturdy box and carried the earthenware pot back into the garden. By the time that he had finished his work I was already almost asleep, but out of the corner of my eye I saw him steal back into the farmhouse and carefully extinguish his work lamp. The room fell into almost complete darkness. The last remaining embers of the fire cast a weak, flickering light. Only now did his day seem to be finally coming to an end.

Basho says that every haiku should convey sabi, which can be loosely translated into English as “loneliness”. He didn’t mean the loneliness of the shipwrecked sailor, or the loneliness of the night watchman who must stand guard at his dangerous post all night long in the cold; he was referring to a loneliness of a different order, a loneliness that is far more tragic and devastating.

If a soldier walks off to battle in a brand new suit of armour, but that soldier is an old soldier with thin legs and white hair, then that is sabi. Or if a young man picks a beautiful rose and gives it to a woman with whom he is in love, but she despises him and discards the rose in a ditch, then the rose lying in the ditch also has sabi. Or if a well-intentioned man lives in an outsize dream but doesn’t realize it, then that too might be sabi. But as hard as I thought about the farmer, and despite what I expected to find, I could detect no trace of sabi anywhere.

I rolled over and turned my back to the dying embers and thought of the brilliant sunshine of the plains that had almost reduced me to delirium, and of the wild fruit trees of the woods whose juices still stained my shirt. I thought of the old monk in the derelict temple, who would now be curled up alone on the cold stone floor, and I thought of the well that stood in the temple yard; and its cool

dark waters that could quench any thirst and, before images faded altogether from my weary mind, I thought of the seedballs nestled in their bamboo basket and the fabulous forests of vegetables that they promised to bring. But most of all I thought of the farmer.

The following day I was woken once again by the sound of the farmer’s busy activity. He was squatting over the hearth, arranging pots and pouring fresh water into the kettle. He must have sensed that I had stirred, for he turned his head to look at me.

“Good morning. Did you sleep well?”

He had flung open the large door to the garden and light was streaming into the room, along with a very gentle breeze that was laden with scents from the fields. I could hear birdsong. I smiled dreamily and then gingerly moved my limbs under the blanket. I was relieved to find that my aches and pains had completely vanished and I was feeling very much less weary.

“Yes. I slept extremely well.”

He continued to potter around, coming in and out of the door to the garden and then standing in the doorway and surveying the view of the garden and fields beyond. I sensed a change in his mood from the day before. I couldn’t put my finger on it exactly, but I felt he seemed more open, more relaxed. As if to confirm my feelings he spoke again with a smile on his face.

“We have had a very good omen this morning.”

I sat up and rubbed my eyes and discovered next to me a cup of hot tea and a bowl of gruel with fresh herbs and vegetables. Hungrily I tucked into the breakfast, wondering what he might be referring to. When I had finished my food he interrupted his activity and came over to me to pick up the empty bowl and cup.

I bowed my head and handed them to him. “Thank you. That was absolutely delicious.”

A radiant smile lit up his face.

One Day the Shadow Passed

One Day the Shadow Passed